If you would like to request an exhibition catalogue please email: cedric@cedricbardawil.com

Discipline of Ecstasy is a solo exhibition of new work by acclaimed figurative painter Paul Housley. Over a forty-year career, Manchester-born Housley has documented the transformations of high and low cultural life in Britain with searingly inventive compositions that interrogate how we consume culture, and how culture is mediated to us in art, cinema, literature, and the public sphere. In this new body of work, in which he tackles subjects ranging from the Mancunian loneliness of L. S. Lowry, unfulfilled desires, elite Scandinavian museums, and the decline of arts education in England, Housley pushes the legibility of the human figure to extremes while always maintaining an uncompromising empathy for his subjects.

Every day is great for me. I dislike rose-coloured glasses. – Mark E. Smith, 2011

What was the temperature on the back of your neck? – Paul Housley, 2024

It all looks innocent enough. A young man in a denim jacket has turned his back away from us, with his hands in his pockets, and stares through the shop window at the wares on offer. Or, equally plausible, he stares from the inside looking out of an extravagantly-sized glass window onto the neon lights and billboards beyond. Sumptuous oblongs of purples, peach-pinks, and indigo seem to dance over his left shoulder. We watch him watching. To his right, I cannot help but see, in the dense and scrupulous mark-making, the unmistakable upper-body of a woman, breasts exposed. Have we have stumbled on a scene of staged illicit desire? Or is this a picture of melancholy reverie, an ode to lost and missing romantic love? This is Paul Housley’s Hotel, 2024, a new work created for Discipline of Ecstasy, his exhibition at Cedric Bardawil. Housley’s paintings represent figures who, above all, desire and are fixed in a state of longing, or at least have the disposition to desire, and are therefore like the rest of us.. They demand our attention. They shatter our complacencies. What happens to a desire that goes unfulfilled? What if we desire something we know to be immoral? Why do we, against ourselves, so often desire what we once had but has since been lost?

In Housley’s Looking at Art Thinking about the Girl (was there ever much more), 2024, we find ourselves in an altogether more salubrious venue: the Louisiana Museum, on the shore of the Øresund Sound in Humlebæk, an hour north of Copenhagen. In Michael Hoffman’s words, this museum ‘was not bought off a skint, warmongering Napoleon for a measly $15 million’ but ‘founded in 1958 in a dazzlingly extended and updated villa … and named for the first owner’s three (presumably consecutive) wives, all of whom were called Louise.’ In Housley’s painting, the perspective is extreme: it’s as though we have been funnelled into a tunnel with fifty-foot walls and a recedingly small exit point. And yet we have no desire to escape. We imagine the artist — almost certainly younger than he is now, perhaps in his twenties or thirties and ruing the loss, or the revelling in the joy, of an absent lover — sat on an interior bench, looking out through the sleek windows onto the tree branches and admiring the extraordinary display of Giacometti sculptures. I am suddenly struck by how much Housley’s figures remind me of Giacometti’s sculptures. They are often painfully thin and stick-like and often seem at the very outer limit and edge of legibility as a human form. But, like Giacometti, Housley’s figures are definitively human, nonetheless, or as Jean-Paul Sartre called them: ‘an art of existential reality.’ If I was to choose a word that Housley’s figures share with Giacometti’s sculptures, it would be mere. They are merely there, just about existing and, on that threshold, they are their own excuse for being. Many of Housley’s paintings are concerned with the disjunctions and antinomies of British cultural life, and seek to document — if not earnestly critique — the decline of the British state. Requiem for the Golden Age of English Art Schools (Homage to Psalter Lane), 2024, is an elegy for a time (the early 1980s) and a place (Sheffield, whose spirit was then being pounded by Thatcher’s de-industrialisation programme) that Housley holds affection for long after it has ceased to exist. In 1983, he crossed the Pennines to study at the now defunct art school just off these steps, the same place that John Hoyland began painting his heaving vortexes in polychrome. Coincidentally, I grew up a stone’s throw from Psalter Lane and have walked up those steps at least a thousand times. Housley’s painting completely reimagines this square that I know so well: surprisingly, the brutalist campus seems to have been designed by Giorgio de Chirico, with seductively neoclassical archways leading off on the right while the drab city centre beyond has been entirely populated by arboreal orbs set against a linen blue sky. As one might expect, the pavement is, in reality, a sad kind of concrete and clay but in Housley’s rendering it is golden and yellow like Vincent van Gogh’s Arles; we want to be there, in the first flush of youth, as we might remember our first days of university, wherever they may have been, with the saccharine nostalgia of Ted Hughes, who works hard against forgetfulness in his poem ‘Fulbright Scholars’: ‘Just arriving – or arrived. […] I was walking / Sore-footed, under hot sun, hot pavements. / Was it then I bought a peach?’ But Housley is less interested in Hughes’ highly individuated mode of recollection. His paintings manage to capture something about how we collectively remember and mourn and grieve and forget. It is entirely English, and provincially English, but has an expansive sensibility that is irreducible to that of a Little Englander like Philip Larkin. Indeed, it would be incorrect to say that Housley is nostalgic for a particular place, a particular vision of an England eroded in time, but it would be correct that he is interested in what has been lost on a national scale. His paintings reanimate the postwar belief in regional cultural life in Britain while at the same time acknowledging the impossibility of that belief being actualised again.

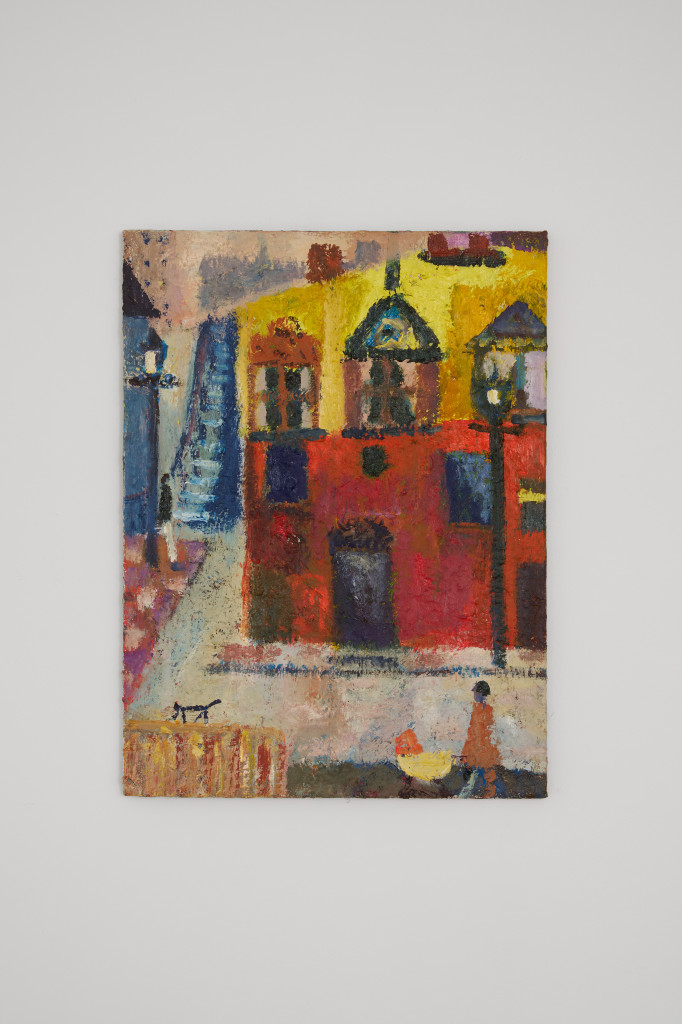

Housley was born and raised in Manchester, and clearly remembers with enthusiasm and clarity that city’s idiosyncratic architecture: its red municipal buildings, its stone and granite, its relentless grey skies. Manchester has always outgunned its place in British culture, the worker bee in its metropolitan imagination. In this vigorously pursued body of work, he has returned — imaginatively, if not in body — to his childhood in Manchester. In The Manchester Years (Little Brother Know Me Well), 2024, Housley depicts a typical Mancunian scene: a woman walks her baby in a stroller while someone else smokes a cigarette leaned against a Victorian streetlamp, both overwhelmed by an orange-red building where sordid activities are almost certainly happening on the other side of its third-floor windows. This is L.S. Lowry for the post-industrial age, an age when Manchester’s once-powerful industries have been decimated; alienation is now the rule, replacing the world that Stretford’s most cherished son observed with pithy joy. Even in Lowry’s bleakest moments, at least the factories were open, and supporters were the lifeblood of the football club; a sense of togetherness was the price paid for a diminished sense of individual agency. An inheritor of Lowry’s sensibility, Housley is one of the most perceptive of contemporary British painters not because he depicts the country as it is, but because he understands what it means to exist in a place where the imagination in the expanded sense of the word offers an exit door to that country as it is. ‘History is not merely what happened’, as Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote, ‘it is what happened in the context of what might have happened.’ Ahistorical and yet resolutely of the world, Housley’s paintings — of Manchester streets and Cheshire fields, of the cinema and visual culture of a lost England — offer a vision of what might have happened in the context of what did happen. It is for this reason that Housley’s paintings disavow the nihilism for which they might readily be accused: they are paintings of possibility more than they are documents of decay.

Of especial reverence in the Houslian canon is Anthony Burgess, the Catholic rogue and triumphant tax avoider from Harpurhey, a suburb of Manchester, who was the son of a drinker, a pub pianist, and a one-time tobacconist. His greatest success, A Clockwork Orange, was published in 1962. In The English in Love (Discipline of Ecstasy), 2024, we find the novel’s anti-hero, Alex DeLarge, and his three droogs preparing for a night of ‘the old in-out’, a euphemism for rape and wanton violence. The figures resemble the geometric logic of David Bomberg’s figures: composed of thin limbs and single-coloured, looking more like girders on a building site than people one can reach out and touch. At its heart, Burgess’ novel asks a fundamental question about our ethical relation to the British state: does the state’s enforcers and psychiatrists have the responsibility, or indeed the right, to destroy Alex’s deeply-held love of Beethoven if it means they can reform him through ever more extreme procedures? What does a reformed British subject look like? Housley’s picture seems animated by a similarly visceral invocation of ethical responsibility. Despite all the real and implied violence of his paintings, we cannot help but feel them Housley’s canvases as tender portraits — of England, of the past, of joy and love — and of how hard the artist needs to graft, then and now, in a society that often stands as a hostile force against the imagination of painting.

Housley’s paintings regularly animate the dialectics between the thinking, reflective artist and the frightened world in which he finds himself. His figures often feature solitary characters in environments that sometimes subsume them, and sometimes elide their subjectivity in a volatile accumulation of paint. In Empire of Light, 2024, the artist is seated on the floor of his chaotic workspace with his elbow resting on his knee in a pose that recalls the history of the genre. If the inspired painter grafting away in his studio has inspired artists as varied as Gustave Courbet, whose L’Atelier du peintre, 1855, depicted ‘the world’ (allegories of Academic Art, as well as Charles Baudelaire, Champfleury, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon) coming to visit the artist in Ornans, all the way to the revisions of Kerry James Marshall and his compositions of African-Americans as both subject and producer of the studio scene, then Housley, too, invites us into the solitary space of paint on canvas, paint on canvas. Empire of Light might be more explicitly self-referential than many of his works, but it recalls his central themes: ‘of course all my work, and maybe all art, is about sex and death’, he tells me. All of Housley’s paintings have those stakes. They are about what it means to be alive, then and now. They are about what it means to be human, all too human.

Exhibition catalogue essay by Matthew Holman