A solo exhibition of new works by Mark Wallinger.

If you would like a preview catalogue, please email: cedric@cedricbardawil.com

From the top of St. Paul’s Cathedral, then the largest architectural vantage point in London, glass balls are dropped simultaneously in pairs, one full of quicksand, the other full of air. Two men crouch over a wooden platform that has been suspended around the cathedral’s balcony, just below the cupola, and held at one end by iron pivots and at the other by a wooden peg, so that the balls can be dropped simultaneously to examine the phenomena of bodies falling in air. From the nave, the two men are directed by a sixty-seven-year-old Sir Isaac Newton, now in the autumn of his life with wispy grey locks all hunched up over a weathered black tunic. It’s June 1710, as St. Paul’s was nearing completion after the Great Fire of London in 1666. Newton, whose theory of gravity had already revolutionised European science, still believed the best experiment involved spheres dropped from significant heights; to follow their course through the air, whether determined by rational laws of motion, aleatory indifference, or by God himself.

Consider what happened next, far exceeding the facts that Newton recalls in his Principia Mathematica. Say, something like this: Newton watches the glass balls fall from their scaffolded height, held in all their possibility of speed and accelerating movement, and now accented by the new Baroque pillars for the new city of London. Once the spheres fall, the glass breaks, dispersing what has been contained across Wren’s black-and-white chessboard of marble. On the one hand, that dispersal was planned and premeditated, the inevitable outcome of what happens when a body in motion is compelled to change its state by the forces impressing upon it. On the other, it represents the impossibility of knowing what will happen next, after the balls hit the ground. However many times the experiment is run, the dispersal will be different. Keep in mind, then, the always possible combination of certainty and chance, of glass and quicksand and all manner of liquids, in the mind of he who not only believes in nature’s laws but who has made it his life’s work to articulate them for us.

With his new sequence of works entitled Motion Studies (2023), Mark Wallinger has envisaged Newton’s project anew; not to measure, or not merely to measure, the distances of bodies in space but to explore the visual capacities of what happens next. The action is swift and explosive, as the ink-covered marbles trace their own movements. The resultant drawings, therefore, describe the physical laws of motion as outlined in various experiments by Newton; the straight lines radiate from their initial collisions until with the loss of momentum occasioned by friction, spin, and air resistance, they begin to describe curves until they come to a standstill.

The outcome of Wallinger’s experiments is dynamic; the lines restlessly reach out to the outer limits of their world while being gently contained within the logic of their reaches’ limits. Indeed, they resemble so much: the word-picture lyricism of Japanese calligraphy written in Kyoto ink; the spilt fountain pen’s porous residues on a frantically-called napkin; even, dare I say it, the gestural mark-making of Jackson Pollock, who used his Najavo sticks out on bleak autumnal days in Springs, Long Island, to dance around the canvas on the floor, creating his ‘drip’ paintings. But if Pollock was convinced that his paintings cohered to the artist’s grandiose desire to embody the unsayable order of nature, then Wallinger positions these works within the scientific tradition of the experiment: the attempt to understand the order of nature by acknowledging one’s inability to understand it in advance.

Wallinger was inspired to produce his series of motion studies by his involvement with St. James’s Church, Piccadilly, another ‘Wren church’ which was designed by the master- builder of the post-Great Fire reconstruction. Today, St. James’s Church is often seen as a politically radical space, placing it within a long tradition that goes back at least as far as the poet and visionary William Blake, who was born in Soho and baptised at there in 1757. It seems entirely plausible, to this writer at least, that these spinning lines of ink speak to Blake’s fierce poetics as much as Newton’s laws. In his poem ‘Auguries of Innocence’, a poem which was part of the ‘science’ section of Poems on the Underground, Blake writes:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour.

In his meditation on how the laws of the world are mediated by the co-implication of the infinitely small and the incomprehensively vast, from the particle to the planet, Blake articulated something akin to Wallinger’s marbles: the force of the universe is profound, and articulates, if nothing else, its own reason for being.

In addition to Blake’s site of baptism, St. James’s Church was Newton’s local parish and where he regularly worshipped; just a stone’s throw from his house at 87 Jermyn Street. Wren’s fabled rebuilding of the destroyed churches of London was an extraordinary achievement. From the ruins of death and decimation, the city rose to even greater triumphs in architecture as in its collective spirit. As I discussed Wallinger’s Motion Studies with him, on a mild spring morning with the works tacked to the wall of his Archway studio, I couldn’t help but feel something of the Londoner’s spirit of rebuilding as a driving impetus for their exciting directions of movement and form. Beside the Motion Studies were a series of photographs entitled Panorama: London 2020 (2020). They depict the centre of London from the locus of the artist’s home in Soho, from Waterloo to Euston stations, taken during the Covid-19 pandemic. With his characteristic inventiveness to always see life — the distracted stranger with whom we share this bizarre city now stalled and halted in motion; the words that are used to explain the extraordinary present and are lit up in twenty-foot lights on Piccadilly Circus — Wallinger imagined the darting trajectories of the people of a city held in stasis. Wallinger’s works remind us that the force and vitality of London, and our experience between dense layerings of history and irrepressible modernity, is never banal, never lazy, never given in advance.

What Wallinger’s Motion Studies remind us of is that, in the very drop of a sphere in space, or in the body of a flaneur walking his city’s deserted streets during a global pandemic, or indeed perhaps in every act of willed movement in a world that has its own laws and logic of finitude, life goes on — and, indeed, so often goes on in greater brilliance than before. If in the Motion Studies it is also possible to read only the visual marks of arbitrariness, of the capricious landing of mere marble on paper, then it’s equally possible to see them as a call to remember, in Freud’s words, what we neglect to be ‘real and immediate.’ Wallinger’s Motion Studies remind us of how much is going on in the world, even on days when nothing seems to happen.

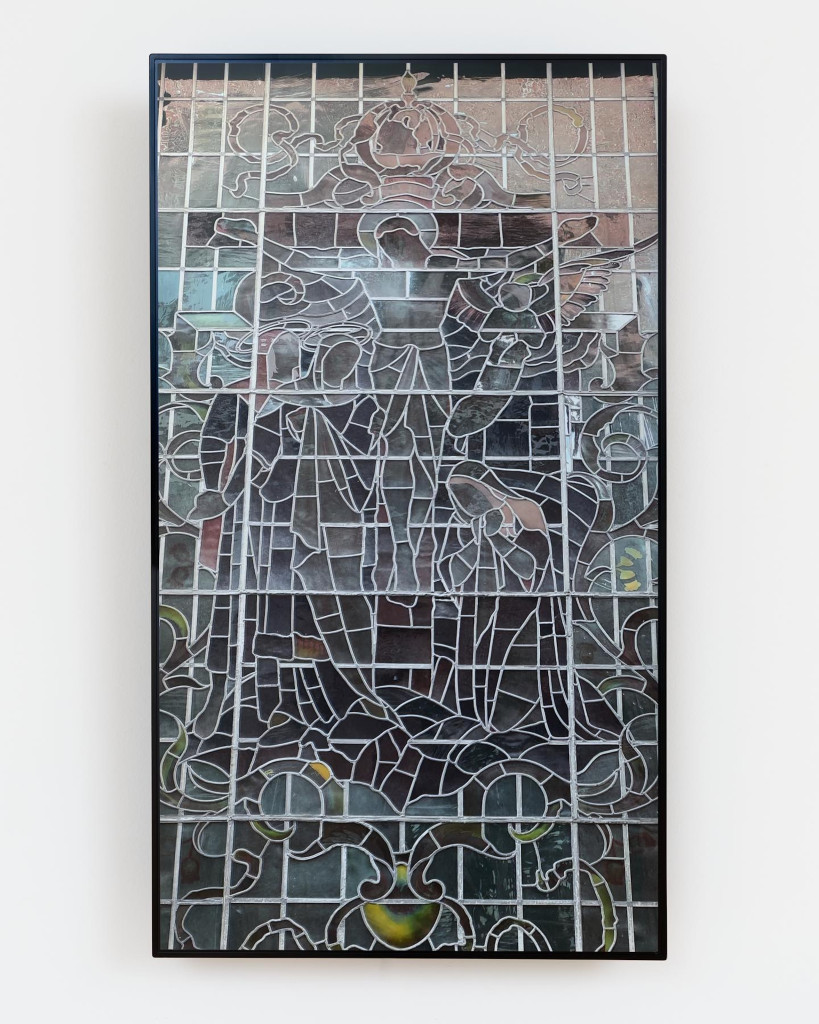

To accompany the works on paper, Wallinger has produced three new video works that reflect on the area around St. James’s. Stained Glass Window (2023) depicts the exterior view of the decorated windows on the south side of the church, which glint with the changing light marking new patterns on the other side of the Biblical narratives of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice. Optiks (2023), named after Newton’s 1704 treatise on colour and light, is another piece that speaks to the counter-side of London, away from its historic Christian devotion and as a centre of global capitalism. As seen from the cranny of a commercial arcade, Wallinger depicts the storefront of Hackett’s tailoring shop on Jermyn Street, the site of Newton’s former dwelling house and commemorated with a blue plaque. Its shop’scrossedumbrellalogosuggestsomething of Newton’s measuring compasses, such as those depicted in Blake’s monotype Newton (1795–c.1805), the video once more shows us a London that is both created by rationality and captivated by the subjective meanings of chance encounters. These videos, taken together and in dialogue with the Motion Studies, are also reminders of London’s accommodation of the sacred and the profane, the place of memory and the site of rampant individualism.

If, in his Motion Studies, Wallinger is explicitly drawing on the seemingly dialectical traditions and visions of Newton and Blake — of the rational worldview that believes everything seen can be measured and cohered within the new parameters of science, and the mystical belief that all things seen are part of an unknowable cosmos of divine variations — then the artist’s reconciliation might also reveal a false dichotomy. When John Maynard Keynes, the liberal economist and member of the Bloomsbury Group, bought Newton’s personal papers at a Sotheby’s auction in 1936, he uncovered several dark secrets. Keynes found that Newton was obsessed with the witching oddities of the occult and the esoteric theologies of minor Christian mystics. After World War II had made it essentially impossible, Keynes’ ‘Newton, The Man’ lecture was finally delivered on his behalf at the scientist’s alma mater, Trinity College Cambridge, in July 1946, and argued that the image we have long held about Newton was a myth. ‘In the eighteenth century and since, Newton came to be thought of as the first and greatest of the modern age of scientists, a rationalist, one who taught us to think on the lines of cold and untinctured reason’, Keynes said: ‘I do not see him in this light.’ Instead, he believed his pursuit of knowledge was driven by a belief that he ‘could reach all the secrets of God and Nature by the pure power of mind, Copernicus and Faustus in one.’ This double-bind, which reconciles the scientist who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its centre, and the tragic figure who bet his future with the Devil, animates the possibilities and constraints of Wallinger’s experiments. If in their delicate lines and sweeping gestures they can tell us anything about our lives, then it’s that they are always held by limits while being thrown into a future that we are completely unable to anticipate.

Exhibition catalogue essay by Matthew Holman