A solo exhibition of new works by Hannah Tilson (b. 1995, UK).

If you would like to request a catalogue, please email: cedric@cedricbardawil.com

‘In the field of aesthetic theory, humans are pattern- seeking creatures’, the American artist Kehinde Wiley has said, a fact ‘that can be seen in terms of musical structures, patternmaking, even in terms of storytelling and literature.’ If London has produced a more compelling artist who has taken up the problem of patterning as subject matter, and transformed it into the most sensitive storytelling, then this writer has yet to find one more brilliant than Hannah Tilson. In her tartan phantasmagorias, cross-hatched dens of retreat and creativity, and pure gingham revelries that seem to envelop all who enter, Tilson asks us questions we can’t hide from. Who are we to ourselves and to others? Or, more specifically, what is the difference between understanding oneself as a ‘who’ (singular, irreplaceable, consistent throughout a long life) and the ‘what’ (the clothes we wear, the gestures we make to those who know us, all that might change and go on changing from youth to senescence)? I hasten to add that we are always, of course, straddling both the ‘who’ and the ‘what’, and yet it is never the fashionable cut of someone’s jib that we remember—deeply remember—in those who move us the most. It’s always, sometimes inexplicably, the ‘who.’ Tilson manages to pattern her images and image-makers wholly idiosyncratically and, while those figures dress as connoisseurs of taste sitting on the floor and stand as snapshots of millennial bohemia, they always manage to speak more to the ‘who’ than to the ‘what.’ Even when they seem to be mostly about modes of dress and self- presentation, guiding us in the fine art of looking damn good, they access the seeming possibilities (and, dare I say, the ultimate impossibility) of knowing another in a profound way.

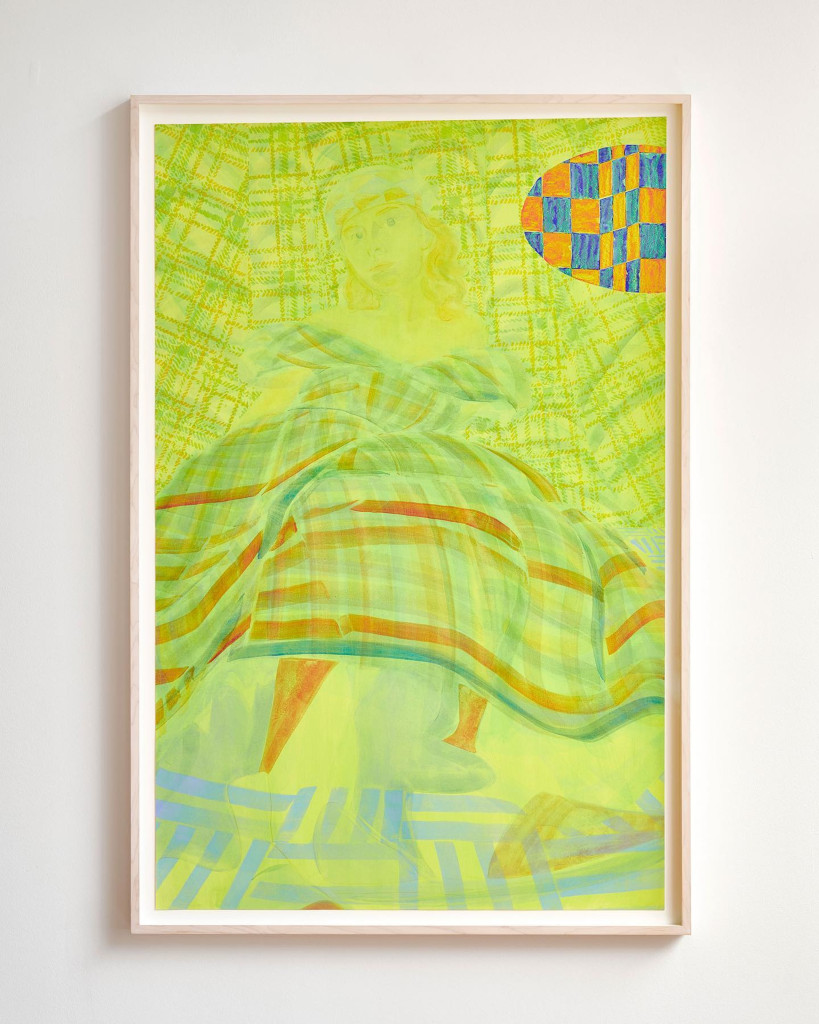

Paintings like Dressed in Borrowed Glories (2023), which appears bathed in lurid green and overlaid in feint tones of textured cloth, is a fantastical meditation on the nature of sight and optics: what happens to the human form when held in tension with the world of visual order (which, from left to right, from corner to extremity, is not much of an order at all). The face that looks back at us is a revised self-portrait of Tilson herself: inquisitive, seductive, not quite hostile. Like Johannes Vermeer, Tilson creates ambiguous atmospheres in which we are simultaneously invited into a private world and inexplicably conscious that we are intruding. We seem to have no reason for being here, but the wild patterns and doe-eyed stares make us glad to be. In one sense, the rich and textured linoleum sections function like a drape, managing to both conceal and reveal the subject behind; staring back at us, we are made to feel both intimate and estranged. Think about Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657). Imagine the dappled ochre drapery in the foreground right wasn’t there. Imagine that we are being read to; that the young blonde girl reading the letter intends to tell us something secret or profane. Now imagine the curtain returned. Tilson’s paintings manage to conjure that same sense of the veiled privacy of a world on the threshold of exposure, but it’s like the curtain both is and is not kept in the room. Like Vermeer’s slow studies, Tilson’s kinetic paintings are compositions that test how far the experience of spectatorship can stand as a measure of ethics: what do we owe, or wish to give, the stranger that we encounter before us? Should we look closer, or look away?

In Razzle Dazzle (2023), the seventies linoleum, which looks stretched between a kind of Moroccan camouflage and the hind patterning of a wild animal, cascades with hard edges in radioactive greens, yellow, and the deepest blues. Laid on a bed, a self-portrait of the artist—changed, altered just, transformed slightly from resemblance—confronts our impertinence. Tilson’s lino- prints are about hand-sized and sometimes incorporate up to four layers per ‘pattern.’ Here, wearing a flowing tartan dress, the figure of Razzle Dazzle gestures to Tilson’s proud Scottish heritage. When the artist took part in a residency at Palazzo Monti, in which some of the most dynamic contemporary artists gather in a 13th- century palace in Brescia for workshops, collaboration, and work, Tilson experimented with filming herself in full tartan garb: ‘I film to allow for unexpected shapes and movements to appear, non-prescribed.’ In these portraits, it feels perfectly accurate that they were originally conceived in motion. The richly textured layering of pattern, cloth, and body all feel deeply absorbed in the nature of the world transformed by time, and the very act of viewership as something always sliding in and out of focus. The tartan is the overwhelming visual principle of Her Body Thrummed (2023).

Seemingly subsumed by the dual flood of both drapery (a bedsheet, a child’s fort?) and clothing (half Renaissance courtier, half Argyle actress?), the figure has retreated into their own solitude. Whether that isolation grants peace or represents the outcome of social antagonism feels beside the point: this has become the figure’s entire world, a world constructed entirely by self-fashioning or make-believe. In Not A Toy: Fashioning Radical Characters, the world’s first comprehensive investigation into the growing influence of today’s character culture on contemporary fashion and costume design, and one of Tilson’s favourite treatises, American historian Valerie Steele celebrates the ‘element of masquerade, or “becoming” someone or something else altogether [is to] to culturally construct the self… Of course, the key element behind the idea of masquerade is the mask, providing the element of animism, or the process of attributing a soul to living and non-living entities.’ Tilson’s figures seem to embody this meaning of the masquerade. We cannot help but attribute living, breathing qualities to these character studies and yet are never fully able to see the face behind these masks of pattern, these veiled checks.

In her use of bold, curvaceous colour and subtle subjectivities of the figures depicted in her paintings, it might be easy to identify the post-Pop playfulness of the Chicago Imagists, whom Tilson cites as an influence after visiting a survey exhibition at Goldsmiths CCA in 2019. ‘Instantly drawn to the rawness of their work and their love of materials’, Tilson saw in the paintings of artists like Christina Ramberg and Gladys Nilsson the unification of the real and the surreal that punctuates her self-portraits. More than that, this series of works offer a formal analogy to the Chicago Imagists and their utilisation of consumer images and sign-making as a coherent flank of their practice to comment on the over- saturation of images in late capitalist society. Formally, for Tilson, what this means is that by combining an intensely bold palette with translucent fabrics, she communicates in a visual vocabulary that takes hold of the unmistakable fallacy of advertising—its sleight of hand, the promise of a life transformed—but speaks softly in art historical references that move between stable definitions of truth and beauty. In this way, Tilson is a born performer. From a very young age, she acted and performed in theatre productions. She wrote fragments of plays and imagined whole words of febrile immersion. Stages. Sets. Actors. When the first lockdown forced all of us to accept our homes as our worlds, then Tilson withdrew into a fantastical world of theatre sets and flamboyant costumes in her East London bedroom. In many ways, this feels like a natural progression for an artist who counts the brighter-than-nature colourism of David Hockney, the syncopated rhythms of Sonia Delaunay, and the folky mysticism of Maurice Sendak as influences. What connects these artists? Stage design, of course, is an often-forgotten aspect of their shared multi- disciplinary practice.

In The Hectic Form of Forgetting (2023), which incorporates pigment in binder, lino printing, and acrylic, and is painted on translucent fabric and paper attached to reverse, Tilson depicts herself—or someone like herself—in another self-portrait, but this time playing the role of some kind of harlequin prince, or Renaissance leading man; or, perhaps, how Rembrandt van Rijn might imagine himself as a child in the dressing room behind a Leiden stage. The cross-hatched hat jauntily balances on the figure’s head: the several layers of the work manage to create a genuine sense of three-dimensional depth. Of course, it is three-dimensional. The figure is at another remove from us, proximately as well as ethically. Here, there is the unmistakable atmosphere of seeing someone being seen. The figure’s expression is overflowing with the vanity and the vulnerability that arrives with not being in total control of one’s self-presentation. It is this, the sense of the self-portrait as the rumination on the porousness between self-identity and subjectivity, that enters Tilson’s painting into conversation with the tradition of the harlequin. Pablo Picasso, that other inveterate maker of stages and costume, was obsessed with the harlequin, the archetypal character of his pink period (1904-1906). Seldom without his pocket-mirror, and so often fashioned with the triangular patterning that adorns Tilson’s figure, Picasso’s harlequin was revised from the Italian commedia dell’arte as physically agile, a snidey trickster, who used his wit and guile to vanquish the masterplans of those of higher social standing. But Tilson’s subject is withdrawn, not self-possessed; reflective, far less mischievous. Spend a moment with their aspect: the piercing eyes seek reassurance while nervously hiding behind the drape which is the security and stead.

Does the face not resemble, in some aspect at least, the broken innocence of Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man (c.1482-1485)? For this writer at least, Tilson has made a painting that in its three- dimensionality and compositional complexity manages to exist across space as well as time: it’s as though we are witnessing the very moment, the very impasse, of youth into adulthood. Few artists have been able to honestly articulate what growing older really means. And yet it has been one of the most essential tasks that artists across the centuries have set themselves. In this self-portrait, Tilson gets closer than most. As Siegfried Sassoon laments: ‘sneak home and pray, you’ll never know the hell where youth and laughter go.’ Sometimes, for the briefest of moments, a painting can tell us.

Exhibition catalogue essay by Matthew Holman